March 19, 2020

I've been paying careful attention to the various government policies implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Having many friends and colleagues in the U.K., I am particularly concerned with the British government's plan of action.

The U.K. government's controversial plan of action

At first, the U.K.'s plan differed from other countries' plans—the government imposing merely a few restrictions on the population, relying on so-called herd immunity. This was a terrible plan; for more information, see this article.

Luckily, the government has now recognized the situation's alarming nature and has changed its approach, based on this report from Imperial College London. The current plan implements a strategy of social distancing, which is essential for avoiding the overload of the healthcare system.

Following the presentation of the original plan based on herd immunity, I spoke to my friend who works for the U.K. government in London. She strongly believed that her government "knew better" and that its decisions were "based on science." Well, as a mathematician and scientist, this really puzzled me for three main reasons.

First, the relevant science in this context (e.g., applied mathematics and applied epidemiology) cannot model the spread of the disease in an exact, foolproof way. Pure mathematics is an exact science, in the sense that everything can be either true or false. Here, what we have are scientific models, which utilize simple assumptions to try to represent reality. Those models often use data combined with numerical simulations to give us a snapshot of the future—i.e., a prediction. This process of modelling introduces many sources of error, such as: modelling errors (i.e., the model is a simplified version of the phenomenon we're describing, thereby potentially omitting significant factors), sample selection bias (i.e., the data is not representative of the population), numerical errors (i.e., the problem solved on the computer is de facto itself an approximation of the model), and software bugs. My point is that modelling gives us some indication of what the future may be, but yields far from perfect results.

Second, research in Academia heavily relies on peer review. Once researchers believe they've come up with a new model and have obtained interesting results, they send their work to a scientific journal. This is the crucial step—where experts chosen by the journal validate or invalidate the model, check the data and verify the algorithms, comment on the results, make suggestions, ask questions, and ultimately decide whether the paper should or should not be published. The model and the numerical simulations that the U.K. government's original plan relied on were never published, even though Prof. Chris Witty said that they intended to publish. More than 500 academics criticized the plan in an open letter. To bypass peer review for one's model and simulations in this pressing time suggests complacency. And to withhold the paper itself from the public is arguably inconsiderate and irresponsible. A politician or an individual blindly believing in science is dangerous, particularly if those beliefs have policy-making implications—as in the current context. In essence, science should not be a dogma.

Third, when the lives of a considerable part of the population are at risk (the worst-case scenario predicted by Imperial College approximates 500,000 deaths in the U.K.), shouldn't a government be especially cautious to protect its citizens? I would rather have a government that potentially overreacts in order to safeguard the health of its most vulnerable people.

A simple model for the exponential spread of diseases

I present in this section a very simple model for the spread of a disease and illustrate how social distancing helps to flatten the curve. This was inspired by this excellent article from the Washington Post.

Here are the assumptions of my toy model:

- individuals are represented by points on a rectangular 2D domain;

- at regular time intervals, they move in a (normally distributed) random direction;

- healthy individuals become sick if they get close enough to sick individuals;

- once they're sick, they'll recover after some time;

- once they've recovered, they cannot get sick again or carry the disease.

Following the Washington Post's article, social distancing is modelled by some random individuals being frozen, i.e., not moving around.

These assumptions are indeed overly simplistic, but I guarantee you that even papers like Imperial College's report use relatively simple models. It's impossible to realistically represent all the interactions between people in a city/country. Of course, it'd be possible to get a more realistic model by, e.g., dividing the domain into subdomains with different densities of population or adding a probability of spreading/contracting the disease.

Numerical experiments

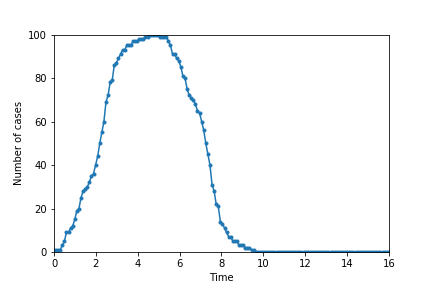

For my first experiment I use the following parameters:

- 100 individuals freely moving on a 10x10 2D domain;

- healthy individuals will contract the disease if within a 0.5 radius from a sick individual;

- they move at speed 5 in a random direction every 0.1 unit of time;

- they recover after 5 units of time;

- there is initially one sick individual.

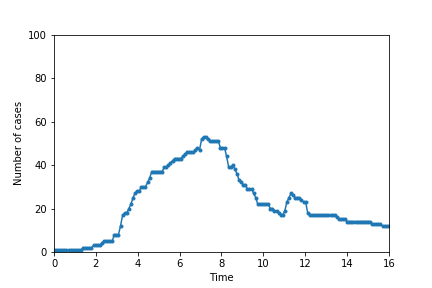

I plot below the number of cases versus time, illustrating the exponential growth of the spread of disease without social distancing.

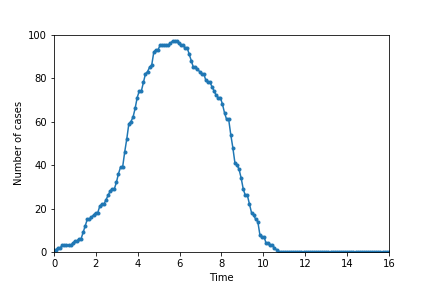

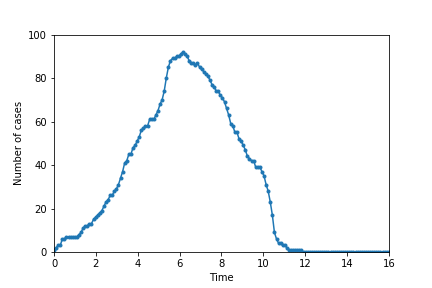

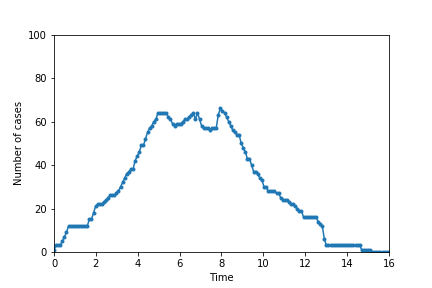

The following pictures show simulations ran with the same parameters as above but with 25 (top left), 50 (top right), 75 (bottom left), and 90 (bottom right) individuals adopting a strategy of social distancing.

The graphs show how social distancing helps to flatten the curve, which is crucial for preventing the overload of the healthcare system. Spread the word, not the disease!

Python code

Finally, to be as transparent as possible—here is the code.